Monday, October 04, 2010

Wednesday, August 25, 2010

Tuesday, April 27, 2010

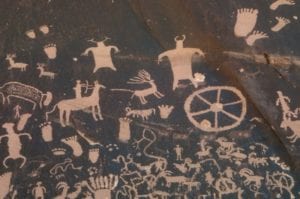

Nican Tlaca Civilizations and Accomplishments

Our true Nican Tlaca heritage is something we should learn about and be proud of. We as Indigenous Peoples to this continent have a great history.

Tlazocahmati to Olin Tezcatlipoca, Nelyollotl Toltecatl and all of Mexica Movement who all made this video possible. Mexica Movement is leading the way towards Liberation for Our People. Visit their website at www.mexica-movement.org . Some of the pictures in this video were taken from the Anahuac Mural, a project of the Mexica Movement.

Visit the Anahuac Mural site at www.anahuacmural.org .

Wednesday, August 26, 2009

Indigenous Perspectives in Global Earth Observing System of Systems

By Paul Racette, posted on April 6th, 2009 in Earth Observation, Education, Featured Person, People, Technology

|

| Dr. Gregory Cajete |

Indigenous scholars around the world are leading a renaissance in understanding of traditional Indigenous knowledge. One such scholar is Dr. Gregory Cajete, a Tewa Indian from Santa Clara Pueblo, New Mexico and author of five books on Native American education, history and philosophy. In one of his books, Native Science, Natural Laws of Interdependency, Dr. Cajete writes, “Native Cultures have indeed amassed an enormous knowledge base related to the natural characteristics and processes of their lands through direct experience and participation.” Dr. Cajete is director of Native American Studies and associate professor in the Division of Language, Literacy and Socio Cultural Studies in the College of Education at the University of New Mexico. He received a Ph.D. from International College – Los Angeles New Philosophy Program in Social Science Education with an emphasis in Native American Studies. Earthzine’s Editor-in- Chief, Paul Racette, asks Dr. Cajete about Native American science and the role Indigenous perspectives have in realizing an integrated Earth observing system.

Earthzine: Describe native science and the natural laws of interdependency?

Cajete: From my perspective, native science really is a body of knowledge that has been accumulated by a group of people, Indigenous people, through generations, that deals very specifically and is very much founded on how that group of people has developed an intimate relationship with the plants, the animals, the places in which they have lived. It is also how the communities have integrated that knowledge within themselves, how that knowledge has been expressed in their language, their art, their music, their dance and their practical technologies for living in places in which they have evolved. Interdependence is a principle that expresses itself in the context of native science. Expressions can be seen in the life of an Indigenous group of people, the ways in which a group of people calibrates their agricultural cycle around key times of observation of the sun with regard to the equinoxes and solstices, how they understand when plants and animals are best to be harvested, when to go hunting, how to serve plants in certain kinds of condition for medicine and how to use those same plants, say for creation of shelter or as food. So there are many kinds of ways in which native science expresses itself in traditional native cultures. You almost have to be very specific in focusing on a particular group of people to be able to understand how the natural world is integrated in their life style and the expressions of cultures of those people.

|

Earthzine: Why does myth and metaphor play a central role in human description of the world?

Cajete: That’s interesting. Myth is really an interesting term because in today’s society, myth is often viewed as a kind of a fable or false story. In native traditions, what are called myths, are better described as stories. Many are called guiding stories that were actually created to teach about something that was important to the people, such as how to survive, how to pick plants at certain times, how to create a context for sustainable hunting practices. The metaphor comes into place in the stories to teach about something else and the something else is really the core teaching of the story itself. Metaphors have been used in a variety of different ways in story forms to convey information and knowledge over generations. Story telling essentially is the first foundation of teaching anything. Human beings are story makers and story tellers.

Earthzine: Traditional Indigenous knowledge is founded on the understanding that we are all related, as in mitakuye oyasin. For some, this is a very difficult concept to grasp. What can you say to help explain this context in which Native science can be understood?

Cajete: If you understand natural systems, to say that everything is related almost goes without saying. I will use an example that I remember David Suzuki presenting in his talks where he uses the example of argon as an element that is contained in the air. They are kind of like tracer atoms. The air that we breathe and that is finite we share with each other right now and eventually we will be breathing those same argon atoms again. The idea is that air is shared by all living, breathing entities and through that physical process we become related to each other. It is using those kinds of ways to describe the fact that physically, socially, even spiritually there is this interconnection and interrelatedness that human beings share with each other and that is referred to by saying we are all related. Mitakuye oyasin is the Lakota way of expressing that idea and that reality. There are words in other Indigenous languages that describe the same thing, that we are all related. We use a term in my language, because corn is kind of our sacramental plant, a staple of our traditional diet, we say we are all kernels on the same corn cob.

|

Earthzine: You write, “We are Earth becoming conscious of itself, and collectively, humans are the Earth’s most highly developed sense organ.” NASA just celebrated its 50th anniversary. Images of Earth from space have transformed the way we view the world. How have images of the Earth, our planetary siblings, our Sun, neighboring nebulae and distant galaxies affected native science?

Cajete: In many ways it helps us to visualize what native science has always been, in one way or another, trying to define, first of all that we are all interrelated, we all breathe the same air, we are made of the same elements of the earth, we are conveyors of the sun’s fire, we are participants in the activities of the biosphere no matter where we are and so this idea of the photographs of Earth, especially the newer technologies that allow us to see the Earth as it is evolving its processes, its weather patterns help us to visualize a living, breathing, active planet processes, the life process of the planet itself. And so those images and ways of understanding ourselves, really do add to the conceptions and perspectives of native science. A metaphor that is sometimes used in native science is “we are all members of Turtle Island”. This is an idea that has been popularized by the Iroquois Confederacy but it is really a notion or an idea that is held by all native tribes. The metaphor describes Earth as a living, breathing, super organism and that we as human beings ride the turtle’s back. The thoughts that we think, the actions that we perform, the understandings and the insights that we gain, the celebrations as well as the sadness that we feel are all registered on the Great Mother of the turtles’ back. And so, we affect the consciousness of the Earth as she affects ours. This idea of the super organism which is the planet Earth has been held by every Indigenous culture that I can remember ever studying and can be said to be the prime philosophy of native peoples. It is the understanding that one comes to naturally; if you are a good observer you can begin to see how life forces interact on the Earth or just in the place in which you live, and you begin to have a sense that there is this greater organism, this greater process that is a part of life.

Earthzine: A principal goal of GEO is to integrate Earth observing systems into a Global Earth Observing System of Systems, GEOSS. What role can Indigenous perspective play in realizing an integrated Earth observing system?

Cajete: Much of the practical day-to-day knowledge of Indigenous people, what is called traditional environmental knowledge, is based on generations of knowledge and understandings that have been passed on through generations by people who live in certain places. Indigenous peoples around the world, living in the places that they do, have knowledge of their places that becomes important data that needs to be integrated into this broader body of knowledge if we are going to understand the ramifications and deal with issues of global climate change. These bodies of knowledge need to be a part of that broader story. We need to create a much larger story of the Earth than we have currently. What we now have is just bits and pieces of a much larger puzzle and so while we are able to see through satellite imagery all of the Earth and the system of the Earth, we don’t necessarily have the details of what is going on in specific places of the earth. The other contribution, before I go on, is one of attitude and one of philosophical orientation. It goes back to the Earth as a living system, as a living entity that deserves respect and deserves understanding and deserves some kind of reverence. Really the message of Indigenous cultures and traditions is you have to have reverence for that which gives you life.

Earthzine: We are all being impacted by climate and environmental change. The impact is now severe for many Native Americans and Indigenous peoples whose life ways are tied to the rhythms of Earth. Are there any needs or gaps that Earth observing technologies or satellite observations can fill for the Native American communities?

Cajete: One way that that technology can be useful to native areas, native reservations, native lands, and native communities, is through providing an understanding of how rapidly change is happening in certain land bases controlled by native peoples. There is a lot of interest among many tribes with regards to the GPS technologies. Tribes that have a large land base are able to see how their land base is changing due to deforestation, drought conditions, flooding or a variety of weather related effects In earlier days, let’s go back historically, the first Europeans found, what could be called the Garden of Eden, an amazing richness in America that wasn’t present in Europe. The tendency at that time was to think that this abundance was just a natural occurrence. We are beginning to understand that the abundance was what today can be called ‘terraforming,’ for lack of a better term, where groups of Indigenous people took care of the places in which they lived to such an extent that they were able to bring those places to an abundance of plants and animals and diversity. Practices of people enhanced living in those places to the extent that it created a bounty of plants and animals that humans could use for food. I know this was true in the Southwest as well because we supported much larger populations than are supported now due to an ability to work with the land in such ways that they enhanced wild food as well as traditionally domesticated foods. What I am saying is, today what the new technologies can help us do is to actually begin to understand our land bases in a much more intimate way, in some ways the way we used to understand them. I see a lot of advantages in technology.

Earthzine: You write, “This knowledge must now be transferred to others and studied seriously by Native and non-Native people the world over for the models and lessons that it can provide as we collectively search for an environmentally sustainable future.” There exists resistance on both sides. How can we lower the barriers of knowledge sharing?

|

Cajete: I think by helping each other to understand the cultural principles that both our knowledge systems operate from. A lot of the misunderstanding on the part of native people is the feeling that Western science is totally antithetical to native philosophy and maybe at certain levels it is. And at many levels there are aspects of Western science that are utilized by native people to enhance their lives. Likewise, consider native people’s regard, understanding and consciousness related to reverence for the land… how we are going to look at it in a generation from now. Is it going to affect our people and the people for seven generations or more? Understanding of an ecological reverence, philosophy and consciousness that guides the generation of knowledge in the context of science becomes very important and a much needed component. We are searching for, if you will, a revitalization of that reverence of the land and that reverence for all living things that we have always had because we wouldn’t be here as human beings if we didn’t have that. To bring it into a contemporary context to be able to then practice a more conscious form of science is what I am looking to. I know that Eastern traditions, Buddhism for instance, are also being explored for the same reasons, that there has to be a kind of consciousness that guides science rather than the consciousness that has guided it in the past. The big question is “how are we going to develop a kind of consciousness that allows us to work the future and work with the natural processes that are part of nature in a way that benefits both us as human beings but also benefits and cares for the finite resource which is the Earth?” Native traditions in their variety of very diverse kinds of ways were able to do that at one time and I think those are the things that we have to rediscover. This is a rediscovery on the part of native people themselves. There is one book that I highly recommend called Beyond Culture and it’s written by a gentleman whose name is Edward G. Hall who was my doctoral thesis chair. He really explored how conflict happens as a result of language and cultural difference and I think we have to begin to learn again a new kind of language of talking to each other that goes beyond those traditional barriers and traditional kinds of issues that we have culturally. Those kinds of bodies of research are very important. For me as an educator, a native educator, there are two quintessential issues that we have to come to terms with. The first one is how we are going to deal with ecological crisis which is an issue of physical relationship, our physical relationship to the Earth. The other crisis is how we are going to deal with each other, which is the issue of social ecology.

Earthzine: It has a spiritual dimension as well.

Cajete: Absolutely, the context is a spiritual consciousness.

Earthzine: You’ve called for a ‘mutually beneficial bridge and dialogue between Indigenous and Western scientists and communities.’ In your eyes, what do you see looking ahead?

Cajete: I see a lot of projects that bring together native communities and the body of native community knowledge with Western scientists working on projects related to issues that are viewed as meaningful and important to native communities. A lot of this is going on already in many ways. So, I think coalitions of Indigenous people are working with interested scientists to begin to address just issues and creating a bridge of dialog between each other. It happens actually in small ways at first in small projects in which there is a respectful and direct relationship around the issue that is established by the Western scientist and by the native community members. I have seen a lot of positive, very beneficial kinds of science being done as a result of that kind of relationship, but it begins with a social relationship, a social relationship that is established first that then leads to trust and then leads to mutual beneficial knowledge. I think those are the kinds of tasks and kinds of teachings that have to happen in the education not only presently, but certainly in the education of the future.

Acknowledgement: This interview was conducted prior to Dr. Cajete’s speaking engagement for the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center’s Science Colloquium on November 21, 2008. The seminar was co-hosted by Goddard’s Native American Advisory Committee for which Paul Racette serves as co-vice chair.Sunday, July 26, 2009

The Extended Mind: Recent Experimental Evidence

ABSTRACT

We have been brought up to believe that the mind is located inside the head. But there are good reasons for thinking that this view is too limited. Recent experimental results show that people can influence others at a distance just by looking at them, even if they look from behind and if all sensory clues are eliminated. And people's intentions can be detected by animals from miles away. The commonest kind of non-local interaction mental influence occurs in connection with telephone calls, where most people have had the experience of thinking of someone shortly before they ring. Controlled, randomized tests on telephone telepathy have given highly significant positive results. Research techniques have now been automated and experiments on telepathy are now being conducted through the internet and cell phones, enabling widespread participation.

Speaker: Rupert Sheldrake

Rupert Sheldrake, Ph.D. is a biologist and author of more than 75 technical papers and ten books, the most recent being The Sense of Being Stared At. He studied at Cambridge and Harvard Universities, was a Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge and a Research Fellow of the Royal Society. He is currently Director of the Perrott-Warrick project, funded from Trinity College Cambridge.

Saturday, April 04, 2009

What story is the place you live telling you?

What animals are out and active?

What plants are awake, what are they doing?

How is the weather?

Which constellations and planets are out?

How are you interacting with all of this?

Connecting to our environement

I invite you to give this some deep thought and to share what you find.

I challenge you to begin to relate to your self and your surroundings in a slower and more personable way than usual. You have the wisdom inside you that you need and if you get stuck, try asking the land and animals that you live with.

What story is the place you live in telling you?

Friday, February 27, 2009

Browning the Greens

http://www.realitysandwich.com/browning_greens

Antonio Lopez

Van Jones’s The Green Collar Economy proposes a “design for pattern” approach advocated by Wendell Berry, with the intended goal of solving two problems -- economics and environment -- with one solution. This method seeks to redress the common trap of designing solutions for singular problems without taking into account the broader, holistic context or source of an issue. By advocating for green tech jobs and training for traditionally underserved communities (in particular the urban poor and incarcerated youth), Jones rightly points out that many environmental programs have in the past been elitist and out of touch with the needs of working class people, and “people of color” in activist parlance. I personally eschew this term, simply because many people, such as myself, are hybrids and don’t fit easily into racial categories (I apologize in advance for my interchangeable use of various terms of differentiation, such as “white” or “Hispanic”). But Jones’s point is well taken. We have to argue for social justice as well as environmental care, without which we will continue to fracture and disaffect our movement. If we are to find the true pattern of ecological culture, we need to see that it’s composed of many hues, and many classes. So far corporations have benefited from our lack of understanding that the war against the environment is also class warfare.

The anti-immigration stance of a Sierra Club faction a few years ago is a good example of environmental elitism being out of touch with the broader population, in particular by alienating predominantly Latino low-income and working class people. Another example is a prominent environmental organization in Santa Fe that, according to an insider, is unselfconsciously anti-human. This has resulted in their work advocating against Hispanic loggers in Northern New Mexico. Ecopsychologist Chellis Glendinning has sided with Hispanic loggers, who traditionally practice low-impact harvesting, but have been caught in the middle between NGO environmentalists and multinationals. Big companies well versed in divide and rule tactics have exploited the tension between Hispanic workers and more recent immigrants, who tend to be affluent white people using the land for recreation, not for subsistence.

The situation in Northern New Mexico bears further investigation. Santa Fe, where I lived for more than 15 years as an adult (my family is colonial Spanish and has lived in New Mexico for more than 300 years), is a rich cauldron of tension between the older land-based cultures of the Hispanics and Native Americans, and the influx of affluent whites. The immigration started after the Mexican-American War with the advance of American settlers to the West, but increased at the turn of the century as New Mexico became known as a safe and aesthetically rich environment for artists fleeing the oppression of industrial and puritanical East Coast life (many of the early émigrés were gays and artists, “black sheep” of their world -- hence my designation of New Mexico as the “land of exile”). From early on whites have paternalistically altered traditional artistic and folkloristic customs to match capitalist market practices (such as creating competitive art markets for traditionally made items for the home or religious purposes). I feel that I can speak with some authority on these matters because for many years I worked as a newspaper reporter covering arts and culture for Santa Fe’s daily paper, which put me in the middle of these social conflicts.

During this time I also got involved with bioregionalism. My entrée into the movement came in 1996 when I attended the First Bioregional Gathering of the Americas in Tepoztlan, Mexico. The congress was a week-long event with participants from all over the Americas, but was hosted by Mexico’s Rainbow Tribe, a decidedly alternative hippie counterculture. Canadian and US bioregionalists have similar countercultural roots, but many didn’t seem to jibe with the multicultural mixing between North and South that ensued. I remember one early morning when a Mexican family placed stereo speakers on top of their family van and blasted cumbia towards the camp. An irate Northerner stormed out of his tent, and summarily smashed the offending speakers on the ground. So much for peace, tranquility and harmony. Though this anecdote exaggerates cultural differences (and glosses over the many counterexamples that took place during that week), it reveals a kind of undemocratic arrogance that tends to emanate from Westernized political organizers.

Mexicans by nature have had to adapt to dominant cultural idioms (they are a hybrid culture, after all). In the case of the camp’s inner conflicts and workings, I observed that many Northerners failed to adjust to local (Mexican) customs, notwithstanding Mexican efforts to accommodate their guests. I’ve seen these kinds of behaviors repeat themselves in Santa Fe, a predominantly Hispanicized city. I recall a conversation with a Buddhist activist there claiming that Hispanics were too ignorant to care about the land. She said this (ignorantly!) despite the fact that descendents of the Spanish colonies have lived there for more than 400 years in a sustainable manner (much longer than we can say of US culture). It wasn’t until WWII that the draft and the advance of “free” markets displaced the land-based communities. Old-timers, such as my grandmother who was born in 1912 (the year New Mexico became a state), grew up on “organic” beans, chile, meat and corn. I put the term in quotes because organic was conventional, not the reverse. She is 96 and a tribute to the traditional lifestyle. Before the war there was little money used. Most people bartered and worked collectively on their farms or ranches. So you can imagine that it’s an utter insult to hear some environmentalists tell the locals that they are too uninformed to practice sound ecological practices.

But culture changes, and fortunately there is much more cross-fertilization going on between environmentalists and underrepresented communities. In fact, the point at which I first came into contact with Van Jones was when the Pond Foundation offered scholarships for Hispanics and Native Americans to attend the Bioneers conference in 2003. I went under the auspices of the Ecoversity, founded by Frances (Fiz) Harwood, an anthropologist who was very sensitive to bridging ecological cultures. I met her at the Mexican gathering in 1996, and worked closely with her for many years. I spent many years with Fiz conversing and strategizing among local Hispanics about browning the greens. When Fiz died of cancer, one of her deathbed requests was that there be a large local party featuring a cabrito (goat roasted in the Earth with hot coals); she insisted that an animal be slaughtered and served at the event. The (white) Tibetan Buddhists overseeing her funerary arrangements (Fiz was Buddhist) were horrified because it would create “thousands of years of rebirth.” The party went on, with red chile seasoned cabrito on the menu.

At the Bioneers conference where I first saw Jones speak, Bronx activist Majora Carter was also there, demonstrating that the Bioneers had crossed the multicultural bridge. The attendees were still largely white, but one evening I found myself congregating with upwards of 40 New Mexican Hispanos and Native Americans who had been brought there by the Pond Foundation. I remember feeling at home in the group, but slightly alienated when we tried merging with the general population. I imagine that people more strongly rooted in their communities find it even harder to adjust to the dominant culture when in general it refuses to budge or absorb from the “bottom-up.”

Consequently, I think one of the keys to Jones’s book is the section in which he critiques California’s efforts to pass Proposition 87 in 2006. Recall that the concept was to tax state oil resources to fund alternative energy research (funny how we designate natural energy as “alternative,” and synthetic as normal). Of course the oil companies pounced on the opportunity to pull “people of color” to their side by arguing (falsely) that their utilities and gas expenses would go up. This was a replay of what I experienced firsthand in 1990 when I worked for CalPIRG as a grassroots organizer on the Big Green Initiative, one of the most ambitious green legislation proposals ever put to the general vote. I recall working in a get-out-the-vote campaign in which I cold-called voter registration lists in West Los Angeles (the affluent part of the city) comprised of 25 electoral districts. I don’t remember if the disadvantaged sectors of LA were being organized, but I do recall very vividly the $25 million ad campaign unleashed by Chevron against us, and feeling helpless because we were unable to respond in kind to their lies about raising the cost of food, fuel, etc. to working class families. We certainly did not have the coalition to buttress that claim. Not surprisingly, victimized by a classic confuse-and-conquer PR blitz, we lost big time. Several years later, though, Latino janitors and maids were much more successful advocating for changes in their working conditions in LA. Too bad the movements didn’t merge.

That heart-breaking experience ended up discouraging me from activism for many years. I imagine that those who invested so much time and money in Prop 87 also felt that way, and worse that they were “outmaneuvered” by the oil companies yet again. But Jones offers a blueprint for survival, and he is absolutely right that it will take a coalition between different sectors of society to get it right. What is most useful in his critique is not the navel gazing that I’ve seen among some environmental activists, but a necessary deconstruction of the practices of the divergent coalitions who have traditionally not worked well (or not at all) together.

Jones argues that the division between environmental and social justice activists falls into three polarities: ecology versus social justice; business solutions versus political activism; and spiritual/inner change versus social/outer change. He calls for moving from opposition to proposition by replacing the “versus” with a “plus,” and to get better at defining what we are for rather than what we are against. The solution -- “three P’s: price, people, and the planet”-- mirrors the corporate responsibility model for the three stakeholder solution of economics, environment and equity. If such a formula were applied to the situation in Santa Fe when environmental activists battled Hispanic loggers -- or even the case of the Spotted Owl, which unfairly pitted workers against the environment -- I believe a more lasting solution would have resulted. Not only would sustainable forest harvesting be encouraged, but traditional land-based cultures would have equity and subsistence, and the rift that has divided New Mexico’s new comers and old would be bridged.

Thankfully lessons are being learned, as evidenced by the Pond Foundation’s efforts to brown the greens, and vice versa. Unfortunately, due to my physical distance from the Obama campaign’s work in New Mexico, it’s unclear to me whether these multihued coalitions are emerging in the aftermath of the election. My hope is that Jones’s well-conceived plan becomes the norm, and not the exception in this turbulent transition to declining economy and rising stakes of environmental degradation.

Image by James Burnes, courtesy of Creative Commons license.

Saturday, January 10, 2009

OyateUnderground New Year’s Message to The Lakota People and The World

OyateUnderground New Year’s Message to The Lakota People and The World from wanbli wiwohkpe on Vimeo.

Raw Footage: An Interview With The OyateUnderground from wanbli wiwohkpe on Vimeo.

Watch the rest of OyateUnderground's Videos

http://vimeo.com/user899792

Wild versus Wall

In the Borderlands-Wildlife and the Border Wall

Wildlife and the Border Wall - This is a video about the wildlife, landscapes and people of the borderlands of the United States and Mexico. It is part of a project I am working on with the International League of Conservation Photographers to highlight the ecological and human impacts of the border wall the United States is currently building along our southern border.

For more information please go to ilcp.com/borderlands

This film details the unique and diverse natural areas along the southern borders of California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas, and explains how they have been and will be affected by current and planned federal border policy and infrastructure, as well as the danger to our rights and safety imposed by sweeping new powers granted to the Department of Homeland Security. A DVD with the long and short version can be purchased. Go to www.arizona.sierraclub.org/border for more info.

Border Wall = Environmental Disaster

I find this as one of the most important wildlife issues of the decade. Actually I find this as important as the drilling in ANWR or the eco mess created at Yucca Mountain. It is a very ignorant mentaliity to think that a 700 mile steel concrete wall will have no impact on the ecosystem or endangered wildlife. The Bush Administration has waivered over 30 environemtal laws to construct the wall. Thats right, the governemnt is violating laws to supposively enforce one. Most undocumented workers come into this country through temporary visas and over stay their visit. This wall will do nothing except bring more migrant deaths to people stranded in the desert, waste hundreds of billions of tax payer money, destroy eco-systems, deplete wildlife and most likely bring animal extinction. It is clear that as long as Mexican and Central American people are living in poverty, that the American economy is in need of low cost labor, and that laws continue to be restrictive then illegal immigration will be inevitable. The 20 billion dollars that the U.S. has spent on militarizing the border in the past decade has had no appreciable effect on immigration levels, but it has caused thousands of deaths and untold human suffering. That's 20 billion dollars that could have been spent on education, foster care, healthcare, alternative energy, or any other productive cause. From a conservative point of view, building a fence and trying to prevent immigration is the last thing from being a fiscal conservative. The cost of building and maintaining a double set of steel fences along 700 miles of the U.S.-Mexico border as much as $49 billion over the expected 25-year life span of the fence, according to the nonpartisan Congressional Research Service. Even if the fence is built it won't do a thing to solve the problems leading to illegal immigration along the southern border. If people are in need they will find a way to cross the border. History has proven that with the Berlin wall, Korea, and other instances in the past. Not only is this kind of policy expensive with regards to money but it has also cost thousands of innocent lives. According to Princeton University Professor, Philippe Legrain, "More than ten times as many migrants are recorded as having died on the U.S. border with Mexico over the past ten years than were killed trying to cross the Berlin Wall during its twenty-eight year existence -- and many believe the true number of deaths along the US -- Mexican border is much higher than the official figures". The number of innocent people dying will only rise as long as the American government continues to build this New Berlin Wall along the Southern border. America is allegedly trying to spread democracy and freedom to other parts of the world, yet, liberty in its very own country is diminishing. How can one call a country, with a wall along its border, a free nation? I believe most of the national enivronmental groups are avoiding this issue because they don't want to lose membership or donations by touching the issue of immigration. A true enivronmentalist would stand up against this attrocity being comitted towards animal life. I think its about high time that Earth First or even the ELF come down to the southern border.

Some interviews by Steev Hise. Other footage is from an episode of Democracy Now, congressional hearings, and the documentary "Earthlings".

Language of the land

In Jeanette Armstrong's article, "I Stand With You Against the Disorder" <http://www.yesmagazine.org/article.asp?ID=1346> she talks about the rootlessness of our modern culture. I was particularly struck by this part,

Check out the rest of the article here . . .

Language of the land

The Okanagan word for “our place on the land” and “our language” is the same. We think of our language as the language of the land. The way we survived is to speak the language that the land offered us as its teachings. To know all the plants, animals, seasons, and geography is to construct language for them.

We also refer to the land and our bodies with the same root syllable. The soil, the water, the air, and all the other life forms contributed parts to be our flesh. We are our land/place. Not to know and to celebrate this is to be without language and without land. It is to be displaced.

As Okanagan, our most essential responsibility is to bond our whole individual and communal selves to the land. Many of our ceremonies have been constructed for this. We join with the larger self and with the land, and rejoice in all that we are.

The discord that we see around us, to my view from inside my Okanagan community, is at a level that is not endurable. A suicidal coldness is seeping into and permeating all levels of interaction. I am not implying that we no longer suffer for each other but rather that such suffering is felt deeply and continuously and cannot be withstood, so feeling must be shut off.

I think of the Okanagan word used by my father to describe this condition, and I understand it bet-ter. An interpretation in English might be “people without hearts.”

Okanagans say that “heart” is where community and land come into our beings and become part of us because they are as essential to our survival as our own skin.

When the phrase “people without hearts” is used, it refers to collective disharmony and alienation from land. It refers to those who are blind to self-destruction, whose emotion is narrowly focused on their individual sense of well-being without regard to the well-being of others in the collective.

The results of this dispassion are now being displayed as nation-states continuously reconfigure economic boundaries into a world economic disorder to cater to big business. This is causing a tidal flow of refugees from environmental and social disasters, compounded by disease and famine as people are displaced in the expanding worldwide chaos. War itself becomes continuous as dispossession, privatization of lands, and exploitation of resources and a cheap labor force become the mission of “peace-keeping.” The goal of finding new markets is the justification for the westernization of “undeveloped” cultures.

Indigenous people, not long removed from our cooperative self-sustaining lifestyles on our lands, do not survive well in this atmosphere of aggression and dispassion. I know that we experience it as a destructive force, because I personally experience it so. Without being whole in our community, on our land, with the protection it has as a reservation, I could not survive.